Remember the last time you had all the facts and figures at the ready to share with someone who wasn’t aware of the facts.

The real facts, about reality, not data based on a belief or an opinion.

Not misinformation.

Remember how it went?

They thanked you profusely - grateful that you took the time to show them the error of their thinking.

They were so pleased they could leave the chat being smarter and knowing what the facts were.

Of course I’m joking, because it’s very unlikely this was their response.

Unless you were fortunate to be talking with someone like Daniel Kaheneman (1934-2024) who became excited when he was wrong because he saw it as a learning experience.

People unfortunately seldom ask questions to become enlightened or transform their thinking - they primarily ask questions to challenge others strongly held assumptions, beliefs and opinions, while believing they have all the answers.

There are many reasons people don’t want to be wrong, including their ego and wanting to belong to their ‘tribe,’ but there’s another reason linked to their nervous system and their neurophysiology.

But first, we need to examine a few other factors before we get down to WHEN people get more open to changing their mind.

The ‘WHEN’ is a clue to the ‘WHY’ people decide to change what they believe.

But before we do that, we need to briefly discuss the scientific method.

Science, Facts and Reality

Researchers are human, and their beliefs and biases can contaminate research and leave it useless at best, and damaging at worst.

Researchers in the social sciences imagine how humans may react, and what results their interventions may result in.

They use these ideas to establish hypotheses and develop experiments to test whether their ideas were accurate or not.

Whether people respond as they thought (hypothesised) they would.

They also control for the variables that may interact with their interventions, so as to better isolate the variable/s that may cause the change.

If we don’t follow such methods we end up not knowing what’s caused the change. We may have to conclude that it’s likely there was a placebo effect, which refers to a person experiencing a positive response to an intervention (eg, a pill, procedure, or therapy) that has no direct physiological effect.

The person thinks the intervention caused the positive response but good researchers know that unless other variables were eliminated (controlled for) the positive effect is likely due to the belief that the intervention was doing something.

Furthermore, maybe something else happened at the same time as the intervention, and that’s the reason for the change.

We’d then have to admit that the result may be due to a correlational effect and that the intervention wasn’t causative.

This is why it’s important to not only understand the statistics that result from interventions but also the limitations that good researchers highlight in peer-reviewed research.

Knowing how to read research is therefore important if you want to knowledgeably discuss experiments because gaping holes in research design can lead to misplaced trust and costly mistakes.

This is the scientific method in action and it helps us reveal interesting and hopefully useful information, which encourages further research.

Why am I going into some detail around the scientific method?

Although we can’t generally extrapolate, or generalise, from one research project to life generally, in some instances we can because the results speak to specific principles that underpin human behavior, cognition, emotions and our neurophysiology.

We may therefore be able to extrapolate from a specific research project, even generalise the results, because the principles are universal to being human.

Let’s discuss one such research project, which given the highly polarised world we now all inhabit, has some important lessons for us all.

This research also appeals to my multi-disciplinary perspective - and first principles approach - regarding mental health, because it addresses cognition and emotion. In other words, even though the researchers don’t mention this, it takes into account that we are embodied beings, and our neurophysiology plays a significant role in our cognition and decision-making.

Political Research Can Teach Us A Lot

Researchers Redlawsk, Civettini and Emmerson had some ideas about how new information about political candidates impacted voters evaluation of the candidates. (1)

As they state in their abstract,

‘In order to update candidate evaluations voters must acquire information and determine whether that new information supports or opposes their candidate expectations. Normatively, new negative information about a preferred candidate should result in a downward adjustment of an existing evaluation …’

However, what they discovered was the opposite.

Voters became MORE supportive of a preferred candidate when they were faced with negative information about that candidate.

The researchers suggested that the voters used ‘motivated reasoning’ as the explanation for this seemingly odd result, with ‘motivated reasoning’ being defined as:

The tendency for us to process information in a way that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs, emotions, or desires. Instead of evaluating evidence objectively, we selectively accept or reject information based on what supports our existing views.

It seems that voters were ‘digging in their heels’ when faced with incongruent/dis-confirming information about their candidates vs. updating their beliefs.

Naturally, we can see clearly that this habit of mind uses a few cognitive ‘tricks’, such as:

Confirmation bias, in which we seek out and give more weight to information that confirms what we already believe.

Disconfirmation bias, in which we dismiss or rationalise evidence that contradicts (dis-confirms) our established beliefs.

However, our emotions are also responsible for what we believe and how we make decisions, which can lead to us defending beliefs, ideas and opinions even in the face of strong counter evidence/dis-confirming facts.

For more on this please see my previous article on Substack, which examined a dangerous feeling, ‘the feeling of knowing.’

Do We Continue to Believe Something Forever, Regardless of Incongruent/Dis-confirming Evidence?

The researchers thought it was unlikely that the voters would continue to use ‘motivated reasoning’ ad infinitum, so they hypothesised that as some point in time people would have to change their mind.

So they decided to test their idea:

‘ … In this study we consider whether motivated reasoning processes can be overcome simply by continuing to encounter information incongruent with expectations. If so, voters must reach a tipping point after which they begin more accurately updating their evaluations …’

They discovered that there IS a tipping point at which incongruent/dis-confirming information tips the voter into updating their evaluations.

In essence, when they decide to take a leap away from what they believe towards new knowledge.

Our Emotions Are Involved … Directly!

First, we need to examine the meaning of a phrase used in this, and other research, namely ‘affective evaluations.’

‘Affective evaluations’ refer to an immediate, generally unconscious emotional response and feelings towards a stimulus, for example, like liking or disliking something, vs. a conscious, reasoned judgment.

There are two things to keep in mind in relation to this phenomenon.

Firstly, it’s an automatic and immediate response, devoid of conscious or critical thought.

Secondly, this response is based on our emotions (and what we call them, feelings) and not on rational, cognitive thought.

Keep in mind, in other posts on this Substack, I mention that emotions travel significantly faster than thought in our brain, which explains why we respond so quickly to anything that elicits an emotional response. (2)

This is also called the ‘primacy effect,’ in which affective (emotional) responses occur before conscious or rational cognitive processing.

So, the researchers understood that the voters were using existing ‘affective evaluations’ - how they already felt about their candidate of choice - to filter the new, incongruent/dis-confirming information they were faced with.

When the voters could no longer defend their belief against repeated negative information. This is also related to cognitive dissonance - when our brain battles to reconcile two conflicting ideas. (3)

The researchers called this point, when enough incongruent/dis-confirming information tipped the voter into thinking differently, ‘the affective tipping point.’

We can think of this as a turning point too.

But, they didn’t know WHEN the point of changing their minds was reached.

Does Incongruent/Dis-confirming Information Impact Our Nervous System?

Other researchers were curious about this issue too, and suggest that our affective (emotional) responses are a result of two emotion-processing systems, namely a behavioral inhibition system and a behavioral approach system. (4,5)

‘ … The first system compares a new stimulus to existing expectations, and if a stimulus is found to be incongruent with those expectations, attention is shifted to it. The new stimulus is thus a potential threat, and this perceived threat generates negative affect like anxiety, interrupting normal (essentially below consciousness) processing …’

This means that our nervous system gets involved in whether we accept incongruent/dis-confirming information. (We’ll get back to this later, but it’s important to this discussion, so keep it in mind.)

These researchers found that anxious voters show more learning and attention to political campaigns, while calm voters pay less attention, and stated that:

‘ … affectively positive individuals (those experiencing pleasant emotions) are more likely to ignore incongruent information, rather than pay special attention to it.’

This led to the logical conclusion that voters feeling anxious and seeking new information would be more rational ‘updaters,’ i.e. they’d accept incongruent/dis-confirming information and consequently update their beliefs.

However, other researchers didn’t find the same results. They found that: (6)

‘ … Highly anxious individuals were more responsive to new information, but overall they were less able to accurately recall information after the fact.’

And, still others found that: (7)

‘ … anxious subjects were more likely to recall information related to the issue in the ads, but failed to seek out more information.’

While still others (8) suggests that positive affect (pleasant emotions) improve cognitive processing.

This contradictory evidence is what led to the Redlawsk et al research, to find out what led to the tipping point of changing our mind, even though they didn’t address the role of the nervous system (neurophysiology) directly.

They state:

‘ … Even anxious voters presumably motivated to learn more and make more accurate assessments may well be subject to the processing biases of motivated reasoning as they affectively evaluate before they begin to cognitively process new information …

… motivated reasoning, suggests that small amounts of incongruent information can be countered in the service of maintaining existing evaluations. The other, affective intelligence, might not come into play until there is a significant threat to expectations, driving up anxiety, and overcoming the motivation to maintain evaluations.

To summarise their ideas, this means we’re likely to use motivated reasoning (which helps us align our current beliefs with new information), with some affective evaluation (how we feel about the information) but only until our anxiety levels rise too much in the face of incongruent/dis-conforming information, which somehow forces us to change our mind.

Let’s briefly examine the research design to give us an idea of what the researchers controlled for and whether we can extrapolate their research to every day life.

Research Design - Brief, I Promise

Redlawsk et al, recruited volunteers in a variety of ways to ensure some diversity, especially in relation to age and income, and 56% of the participants were female.

Participants were randomly assigned to experimental conditions and instructed to select a preferred candidate from a set of options in which they were initially provided with mostly favorable information, which reinforced their initial preference.

Participants evaluated these hypothetical political candidates in a computer-based simulation and received a gradual stream of information about them, using a dynamic information-processing framework that simulated political decision-making.

Subjects were given a chance to practice with the dynamic process-tracing environment and then began the primary campaign where they had 25 minutes to learn about the four candidates in their party, after which they voted for one of them.

As the experiment progressed, and depending on the group they were in, participants were exposed to varying levels of negative information about their chosen candidate.

The researchers:

Tracked real-time decision-making by monitoring how the participants processed and responded to incoming information.

Looked for signs of motivated reasoning (resisting negative information) and what the ‘affective tipping point’ was - when participants changed their mind.

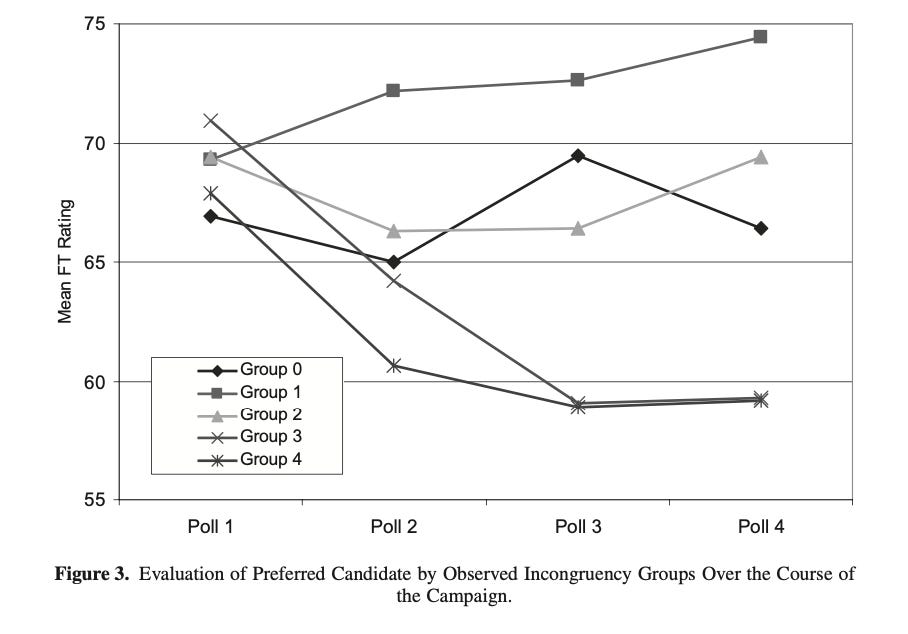

Participants were randomly assigned to five levels of incongruent/dis-confirming information so the researchers could compare whether different levels of exposure impacted the tipping point:

Group (0) viewed candidates who were assigned issue positions that remained ideologically consistent throughout the simulated campaign.

Group (1) 10% of information made available was manipulated to be incongruent with the subject’s own preferences, while 90% of the information remained consistent with the candidate’s established ideology.

Group (2) there was a 20% probability that available information would be incongruent with the subject’s preferences with 80% remaining ideologically consistent.

Group (3) exposed to 40% incongruency.

Group (4) exposed to 80% incongruency.

Enough Already - What’s the ‘Affective Tipping Point’ Percentage?

Unsurprisingly, in Group 0 there were no shifts in candidate evaluation because the participants weren’t exposed to any information contrary to their current beliefs and opinions.

However, in Group 1, where 10% of the information made available was incongruent/dis-confirming, there was also no shift in candidate evaluation.

In Group 2, a similar result was found: no significant updating of candidate evaluation.

In Group 3 and 4 the researchers found a decline in evaluation over time.

So, participants only changed their mind about their preferred candidate when they were exposed to between 40 - 80% of incongruent/dis-confirming information.

And although this is sobering, the next result is even more so, with the average of 20% incongruent/dis-confirming information leading to an increase in positivity towards the preferred candidate.

As the authors state:

‘ … with attitude strengthening effects evident in the face of incongruent information.’

In other words, up until a specific amount of incongruent/dis-confirming information was encountered, such information lead to an INCREASE in attitude strengthening effects.

Participants dug their heels in, and became MORE convinced that their preferred candidate was worthy of their positive support even when faced with contrary evidence, if it was under 20%.

Redlawsk et al, go on to suggest that:

‘ … in these data once about 13% of information about an initially preferred candidate is incongruent with a subject’s own preferences, evaluations stop becoming more positive …

But evaluations of candidates do not actually become more negative … until about 28% incongruent information is encountered.’

Back to Our Nervous System …

We know from other research that anxiety impacts cognition and decision-making in a number of ways. (9, 10))

The Redlawsk et al research suggests that our level of anxiety plays a role in when we’ll change our mind.

When our anxiety becomes too uncomfortable - as we head towards the 28%+ incongruent/dis-confirming level - we may start to shift our thinking to lower our anxiety.

However, up until that point our anxiety isn’t uncomfortable enough to nudge us to change our mind, and so we won’t update our belief or opinion based on the facts we encounter.

Instead, we engage in more motivated reasoning, to actively dis-engage with any incongruent/dis-confirming information when we’re at a lower percentage of this type of information, because that keeps our anxiety levels low.

It’s likely that this affective, neurophysiologically-based ‘litmus test,’ our anxiety, is used in ANY scenario where our firmly held beliefs and opinions are being challenged.

Why?

Because we don’t only engage in this type of motivated reasoning and affective evaluation in political discussions.

We use this type of cognitive PLUS emotional reasoning in any situation that challenges our well established beliefs, opinion and values.

And because our brain and body prefer equilibrium to the opposite, we’re driven to maintain equilibrium by avoiding information that increases our anxiety.

Until the anxiety becomes intolerable, which forces us to change our mind.

This brings us directly to why this research matters today, and why you shouldn’t try to change someones mind.

Five Reasons Most People Can’t Change Their Minds With Ease Today

What are the chances that you’ll have an opportunity to share more the 28%, and closer to 40 - 80% incongruent/dis-confirming information with anyone?

Here are the five main reasons most people aren’t ever going to be exposed to the ‘tipping point’ of changing their minds, or want to be exposed;

People are no longer exposed to dis-confirming information because algorithms provide us with information that we’re comfortable with. In addition, we choose to watch legacy news that aligns with our world-view and other online platform algorithms pander to our chosen perspective too.

A world view that already aligns with what we believe.

What we ‘feel’ is the truth.

If somehow we’re exposed to something that doesn’t fit into that belief or opinion ’bubble’ we can quickly scroll away from it, or ‘dislike’ it, while we continue to train the algorithm to cater to what we want to believe.

We seldom reach the ‘affective tipping point’ because we never allow it to occur.

Critical thinking isn’t taught in most schools or higher educational institutions, so people aren’t able to ask questions about the information they’re exposed to.

Too many people don’t know how to inquire and critically examine where information comes from, or anything else that’s relevant to a discussion.

This is one of the reasons many people are confused about the difference between correlation and causation.

Many people have been led to believe that our emotions, and what we call them, our feelings, are more important than facts or reality.

When we are immersed in our feelings we aren’t able to think critically, even if we have the training to do so.

This is because the brain is either in an ‘action orientation’ OR a ‘state orientation.’ An action orientation means focusing on a task with no thought to our current physical or emotional state. A state orientation means we’re thinking principally about ourselves.

This is why it’s not possible to discuss something that requires cognition when someone is in an emotional state.

When people are exposed to information that doesn’t confirm their beliefs or opinions they feel uncomfortable. Feeling uncomfortable about an idea is a feeling that we have to be taught to tolerate while we contemplate an idea or fact that’s feels uncomfortable.

And as you now know, before we’re exposed to the affective tipping point, we’re going to feel uncomfortable about the dis-confirming information we’ve been exposed to, but not enough to change our mind.

So the natural response is to step away from it and once again immerse ourselves in ideas that feel comfortable.

And, most people are unused to experiencing incongruent/dis-confirming information because they’re seldom exposed to it, so when they are they may experience an exaggerated emotional response.

We’re primed to stay with our ‘tribe,’ the people that believe what we believe because, based on our ancient drive to survive, we feel safer with those we know and trust.

This means that we’re seldom exposed to people who could expose us to information that doesn’t confirm our world view.

And when we are, we simply step back into the comfort of belonging to our tribe, which is as simple as a click on our phones.

Finally, we are likely to have little neural energy to attend to any information that requires critical thinking and evaluation because we have too much information to attend to today.

We’re inundated with information, trying to figure out what to pay attention to, all of which requires neural energy.

As Redlawsk et al. discovered,

‘ … The results show that processing time for incongruent information was more than 10% greater than for congruent information.’

Therefore, even if we’re seldom exposed to incongruent/dis-confirming information, when we are, we’re less likely to examine it objectively because of a lack of neural energy to do so.*

In summary, we’re exposed to less incongruent/dis-confirming information because of technology and our tailored algorithms, we’re no longer taught to be critical thinkers, we’re not comfortable with uncomfortable ideas, we’re seldom exposed to people who have ideas different to those of our tribe and we’re mostly lacking in neural energy.

In combination, these five factors mean we’re less likely to ever be exposed to the amount of incongruent/dis-confirming information required to change our mind about anything.

We could be 100% wrong about an issue, and never know, because we’ve insulated ourselves so well from information that could confirm our confident ignorance.

»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»

*To read more about neural energy and why it’s critically important please check out the article below:

References

(1) Redlawsk, DP and Emmerson, KM (2010) The Affective Tipping Point: Do Motivated Reasoners Ever “Get It”? Political Psychology Vol 31, no. 4, pp 563 - 594.

(2) J LeDoux, J. E (2002) Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. New York: Viking.

(3) Festinger, L. A (1957) Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford: Stanford University.)

(4) Marcus, G. E., & MacKuen, M (1993) Anxiety, enthusiasm, and the vote: The emotional underpin- nings of learning and involvement during presidential campaigns. American Political Science Review, 87, 672–685.

(5) Marcus, G. E., Newman, W. R., & MacKuen, M (2000) Affective intelligence and political judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

(6) Holbrook, R. A (2005) Candidates for elected office and the causes of political anxiety: Differentiating between threat and novelty in candidate messages. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

(7) Brader, T (2005) Striking a responsive chord: How political ads motivate and persuade voters by appealing to emotions. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 388–405.

(8) Isen, A. M (2000).Positive affect and decision making. In M. Lewis & J. Haviland-Jones (Eds.). Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 417–435). New York: Guilford.

(9) Robinson OJ, et al (2013) The impact of anxiety upon cognition: perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Front Hum Neurosci;7:203.

(10) Hartley CA, Phelps EA (2012) Anxiety and decision-making. Biol Psychiatry;72(2):113-8.

Further reading:

Ditonto, T, Mattes, K, and T Jeffery (2025) Are Citizens Politically Competent? The Evidence from Political Psychology; Political Science and Public Policy; Handbook of Innovations in Political Psychology; https://doi.org/10.4337/9781803924830.00018

McRaney, David. (2023) How Minds Change: The Surprising Science of Belief, Opinion, and Persuasion; Oneworld Publications: United Kingdom.

Grant, Adam (2021) Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know; Viking (Penguin Random House): New York.

Dr Linden, M: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael-Linden-4

A well researched and practical article that illustrates both the significant dangers of not teaching critical thinking early and often and the deeply rooted difficulties in being objective. It offers signposts for recognizing our own automatic reactions and then evaluating thoughtfully.

I permanently swore off trying this past October. My life has been so much more peaceful.